This blog on design is the second in my Back to Basics series. My first blog, Gathering Requirements, focused on why network will be built, the design shows what will be built.

This blog on design is the second in my Back to Basics series. My first blog, Gathering Requirements, focused on why network will be built, the design shows what will be built.

As you may recall, ACME Corporation is the world leader in manufacturing rocket-powered roller skates, jet-powered bikes, giant rubber bands, giant slingshots, as well as various types of bombs and dynamite.

ACME Corporation is large enough, and this project is high profile enough, to warrant a design team rather than having one network architect be responsible for the entire design. Additional team members are one junior network architect, one network operations resource, one security resource and one business analyst. Resources from various applications teams, as well as resources from other infrastructure teams, will be consulted as required.

Your responsibilities as a senior network architect are two-fold. One responsibility is to mentor the junior network architect. Your primary responsibility is to have the team create a network design that meets all mandatory and as many of the optional requirements all while staying within the bounds of the constraints.

Let’s get started.

The Deliverables

Significant projects at ACME are subject to extra scrutiny. For the design team, this means two documents are produced, presented to the project board and approved before work can continue.

The first document is the high-level design. Commonly referred to as a conceptual design or macro design, this document provides an overview of the system. It contains block diagrams and is mostly nontechnical. This document provides an opportunity for stakeholders to visualize the system and provide feedback without causing too much rework if the design team needs to make modifications.

The second document is the low-level design and is commonly referred to as a detailed design or micro design. This document is highly technical and includes all the components of the system, along with their features. Once approved, a well-written low-level design is an essential input to the deployment phase of any project.

The Design Process

Workshops and meetings with the design team are crucial to disseminating pertinent information to everyone. Brainstorming at whiteboards or smartboards allows everyone to have input into each document. Because everyone on the team needs to be creative, allow time for them to find their inspiration. Some members will excel at working in a group setting while others will make more progress on their own. Allow for varying degrees of both.

It takes imagination and creativity to produce a network design that meets business, application, legal, technical and security requirements while being bound by various constraints. While it might be possible to implement a cookie-cutter design from a favorite vendor, often customizations are needed.

So, where does one go for inspiration? Allow yourself to be distracted through some mindless physical activity. Go for a walk or a run, mow your lawn, shovel snow, take a shower. All these activities offer distractions for the brain and provide a break from being fixated on the problem.

Five Design Considerations

The goal of the network is to meet business requirements. These requirements usually boil down to characteristics that are commonly considered in all network designs.

1. Availability. While network availability is an industry term and a metric that can be measured, the business only cares about availability in the most general sense. Are the critical applications available when needed? The design needs to account for the required level of reliability (accounting for failures), availability (accounting for failures and planned maintenance) and resiliency (ability to provide an acceptable level of service during a fault).

2. Scalability. How much and how fast will the network grow in the future? Scalability is commonly achieved through a combination of hierarchy and modularity.

Hierarchy: One needs to look no further than a corporate structure to see an example of how hierarchy adds scalability to a system. ACME Corporation has 10,000 employees. Without hierarchy in the organizational structure, Porky Pig, the CEO, would have 9,999 direct reports. Since no CEO can scale to that level, a set of 14 vice presidents report directly to Porky. Each VPs also has a small collection of direct reports that adds another layer of hierarchy and scalability.

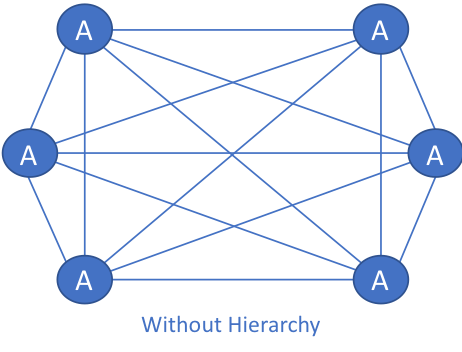

This same principle applies to networks as well. In the figure “Without Hierarchy,” each A node has 5 connections, 1 to each of the other A nodes. If an additional A node is needed in the future, all other A nodes need to be modified.

In the figure “With Hierarchy,” the B nodes add a level of hierarchy to the network. Adding an A node in this network means that only the B nodes need to be modified. The network with hierarchy is more scalable than the network without hierarchy.

3. Modularity. Turning back to the corporate structure for a moment, one can see modularity across divisions of the business as well as modules inside of these divisions. A VP heads each business division. Under each VP is a layer of Executive Directors (ED). Under each ED is a layer of managers. Under each manager is a layer of team leaders who eventually have regular employees as direct reports. One or more modules of this structure could easily be added if new lines of business are created or if existing lines of business are expanded.

Similarly, modularity in networking provides simple building blocks that when combined create networks that can scale by simply adding more of the same building blocks. In the diagrams above, the A and B nodes could represent individual network components. The A nodes could represent an aggregation block inside a data center while the B nodes could represent the cores. Expanding, even more, The A nodes could represent smaller points-of-presence (POPs) across a geographical area while the B nodes represent larger POPs.

4. Security. As a network will always be attacked at its weakest point, it’s essential to design for all three aspects of network security.

Data-plane security deals with network admission, encryption and firewalls. Because many applications provide various forms of security, data-plane security is generally not the sole responsibility of the network.

Control-plane security deals with aspects like routing protocol and first-hop redundancy protocol security.

Management-plane security deals with direct access to the network devices and the systems that manage those devices.

5. Manageability. Manageability is listed last for a good reason. It is vital to avoid being operationally selfish when designing the network. The prime directive is to meet business requirements as it does not matter how easy it is to manage the network if it does not meet these requirements. It is only after the network has done everything it can to assure the success of the business that ease of management and network operations gets consideration.

The exception is visibility toolsets. Health monitoring, capacity planning, logging and packet capture tools, to name a few, will go a long way to support the business and its applications.

Is There an Echo in Here?

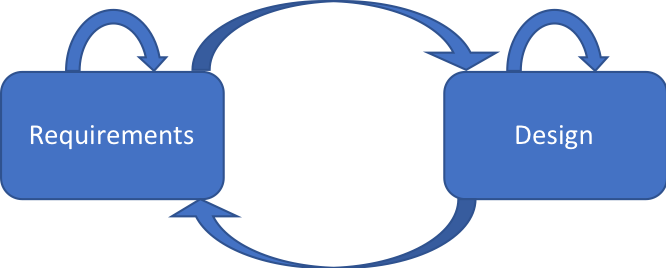

The goal of the design phase is an approved low-level design document. Several iterations through high-level and then low-level workshops and meetings are all meant to fine-tune each document. It is rare to get everything correct on the first pass.

With that in mind, be prepared to go back to the Gathering Requirements phase to clarify requirements. Something that didn’t make sense when first heard may start to make sense after it’s echoed a few times.

Rather than a waterfall approach or a straight line through the phases, expect the paths to be well-worn in both directions and resemble the diagram below.

Read My Other Blogs in this Series