Some people thought that this COVID-19 stuff would have long frizzled out before any technology thrown at it would even be fine-tuned or matured. They couldn’t have been more mistaken.

Some people thought that this COVID-19 stuff would have long frizzled out before any technology thrown at it would even be fine-tuned or matured. They couldn’t have been more mistaken.

Like any other war, desperate times lead to new and great innovations. Back in April 2020, The University of Cambridge (UoC), AstraZeneca (AZ) and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) started to collaborate, setting up one of only six lighthouse test labs (LHTL) that support the UK’s national COVID-19 testing effort. The centre was set up at the Anne McLaren building on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus, where they run up to 25,000 PCR tests per day. The University has had access to a small fraction of this testing capacity in order to provide innovations in the approach to COVID-19 diagnostics. They decided to focus on students living in university accommodation, a population that has seen some of the highest rates of COVID-19 globally, leading to large outbreaks and, in some cases, closure of university campuses.

The problem that the University of Cambridge faced was that with up to 16,000 students to test on a weekly basis, but access to only 500 tests per day, the maths simply wouldn’t add up!

So the novel method of pooling screening samples was adopted to address this challenge. Simply put, specific groups of 2 to 10 students, typically within a household, residence floor or similar, are identified as a pool. They are all tested once a week, with all samples mixed together (pooled!) at the time the swabs are taken, and then tested in one go. This allows for many more individuals to be tested with the smaller batch of available PCR tests. If any tests come up positive, then all the individuals within that pool would be tested separately, and appropriate isolation and quarantine measures are taken around the impacted households.

It’s worth noting that no other university is doing anything like this in the UK or even around Europe, or to this scale, as far as I know, as access to PCR tests isn’t that easy or cheap, and there are significant logistic challenges involved.

The results have been extremely encouraging, showing that this level of testing has been very effective in reducing the spread of COVID-19 around Cambridge.

“23 And Me” for the COVID-19 Family

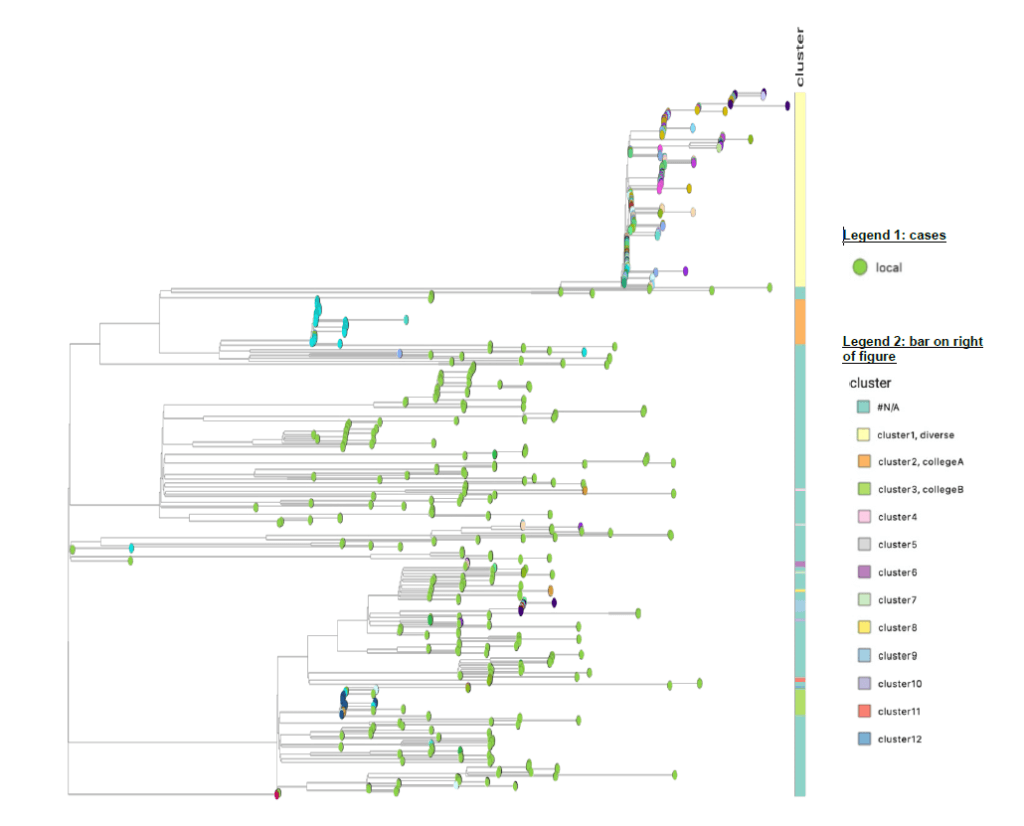

We all know now, that the virus mutates and evolves rapidly. So, amazingly, by genetically sequencing the genome of the virus in the case of positive tests, scientists in Cambridge have been able to correlate each “viral family” and trace the lineage back to specific pools or households.

The approach, therefore, provides even more insight into who may be transmitting the virus and where, so that enhanced infection control measures can be applied.

So What’s Missing?

Genealogical mapping is extremely effective in identifying potential spreading events or locations. These could be a particular lecture or lecture theatre, unauthorized gathering during fresher’s week, or even a market place or shop. So they can become powerfully forensic. There are many scientific papers written about this, and one in particular, has just been published by Dr. Ben Warne, Clinical Research Fellow and the clinical lead for University of Cambridge asymptomatic screening programme.

However, when focusing on a specific population [students] for regular mass testing, you need to be sure that as many people are participating as possible – if not, people like Ben need to understand why. After students left the University for their Christmas vacation in December 2020, they were put under national lock-down on the 4th of January 2021 and many could not return to the city. Suddenly, instead of 16,000 students testing each week, there might have only been 4,000 present. Government criteria for which students could return changed frequently and many students decided to stay in Cambridge over the vacation. With no centralised database recording the location of students, there was therefore a huge level of ambiguity introduced into the results of the tests and their impact, due to the simple fact that the team no longer knew who was actually present or if they were really providing the samples. Surveys which collected student feedback and confirmation of the completion of each test, were not proving effective. Basically, they could have been anywhere in the country, but claim that you had provided their sample for that week! Hence, the unnerving anomalies!

The academics and the University were clearly very keen to continue the study, but they soon realised that there were some important denominators missing; the size of the sample population, time, and location.

IT to the Rescue!

For Jon Holgate, Head of Infrastructure at Cambridge University, and the Cambridge City Council, having a Connected Cambridge with flawless Wi-Fi coverage, has been a multi-year ambition and a very successful one. The University and City Council collaborate in order to ensure all corners of the city are covered, in order to provide secure access for eduroam users and seamless access for the public, in the university grounds and the city areas alike. With over 7,000 Wi-Fi access points, and growing, peppered around the city and in the colleges, Jon Holgate and his team, deliver a robust service to all the subscribers of this service (the city and most of the 31 colleges). The colleges which don’t yet subscribe to the “central” service, all have their own environment, and these are all based on the Aruba architecture, secured through Aruba ClearPass Policy Manager and managed by Aruba AirWave Network Manager.

Leveraging this architecture and the huge amount of valuable network data that it provides, Jon and his team came to the rescue and were able to provide the missing denominators, starting with presence data.

The new information was able to establish whether someone was actually an authorised presence, or if the individuals who claimed to be present were actually there. It is important to point out that in compliance with privacy and GDPR, all data is anonymised. So the team basically check the presence of authorised devices such as mobile phones, laptops or tablets. Many intelligent data scrubbing activities help to make this information more effective. For instance, multiple devices authenticated to one person are counted as one, unless of course they are detected in different locations!

The University IT Services can establish such information to within 97% accuracy from their widely deployed Wi-Fi platform (where devices are connected to the centrally managed infrastructure). The data does not include that from colleges whose Wi-Fi services aren’t delivered by the central IT services. However, students from those colleges, will be detected (through their devices) when they roam around the city or other university premises. The accuracy of presence detection for that population still comes in to within 86%.

Further fine tuning and optimisation of such a method can be possible for the Cambridge team, by looking into the rich data sets available to them from the Aruba Analytics & Location Engine servers (ALE). Jon Holgate and his Head of Wi-Fi Infrastructure, Alexander Cox will definitely be looking into how this data can be used for further enhancements. “One thing is for sure; this methodology and the injection of network data into the mix has been a real eye-opener for everyone in Cambridge”, reflects Jon Holgate. It will no doubt be a significant contribution to the other universities in the Russell Group, and beyond.

The utility of such network-derived data can have many other applications beyond managing epidemics, such as security (detecting the presence of ineligible individuals pretending to be students), optimising student and staff services through correlations with crowd maps and much more. This exercise has shown how important and valuable such data is to an organisation.

Latest Research

Dr. Ben Warne is an academic physician at Cambridge, training and specialising in infectious diseases. Ben was in the middle of his PhD when the pandemic struck. He quickly became involved in research with the hospital and the university on how routinely collected data from asymptomatic testing can help improve the way the pandemic and the spread of the virus could be managed, and reduced more effectively. Ben and his collaborators realised, very early in the process, that the lack of an accurate view over the numbers of present students was a source of uncertainly in their research results.

It was through conversations and close collaboration with Jon Holgate and the University Infrastructure Services team (UIS), that the Wi-Fi and network data turned into a golden asset.

“The pandemic showed us that data is key,” Ben reflects, “the higher the accuracy of our data, the better the conclusions and interventions that we can put in place.”

The weekly tests and results are reported weekly to the universities community, the Department of Health and Social Care, and to the UK government.

In his research and an upcoming paper, Ben concludes such measures and the resulting data, help put in place better conditions for students and staff, and more effectively inform national policy.

The Cambridge Data

The UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, and his team have been providing regular, and sometimes daily COVID-19 updates to the nation. So validating the results and ensuring that they are statistically sane, is a significant responsibility. Thanks to Jon Holgate and his team’s intervention, and thanks to the close work between IT and “the business”, the collaborators are truly using the technology available to them to, as we say in Aruba “Define Their Edge”!

While Cambridge is not the only university to run mass screening, it has some of the most comprehensive data on participation and benefit to students and the surrounding community of anywhere in the UK.

This goes to show how we sometimes don’t know what data we have at our fingertips and how we fail to imagine what we can do with it. This experience has clearly highlighted the opportunities for any organisation to securely leverage their networks for future initiatives beyond pandemics and for numerous other services.

Acknowledgements: With huge thanks to Dr. Ben Warne and Jon Holgate for their time in sharing this insight.